In 1982, a new comic was launched in Britain, the impact of which is still being felt today.

Despite only lasting for 26 issues before folding amidst a quagmire of litigation and missed opportunities, Warrior stands alongside 2000AD as one of the finest anthology titles of all time, firmly announcing the arrival of one Alan Moore.

The Northampton writer had already made a name for himself with an increasingly brilliant run of short Future Shocks in the Galaxy’s Greatest Comic, but it was his contribution to Warrior that ended up changing the face of modern comics forever.

It was there where he created V For Vendetta with David Lloyd and updated the 1950s British hero Marvelman with Garry Leach, both of which have been talked about and lauded massively in equal measure ever since.

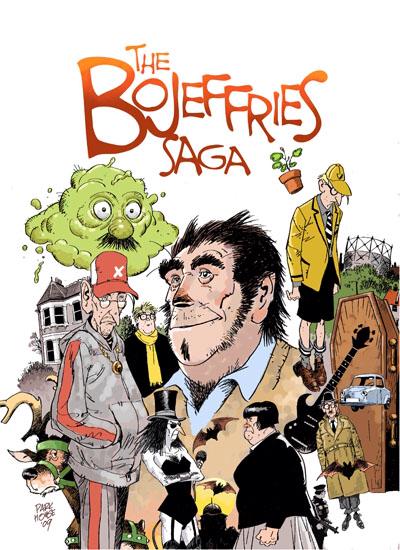

There was a third classic Moore strip in Warrior, though. Making it’s first appearance in issue 12, The Bojeffries Saga was a humour strip, rendered in beautifully timeless cartoon style by Alan’s close collaborator Steve Parkhouse.

Set in a suburban council house in contemporary Britain, Bojeffries was a deft mix of wry social commentary and laugh out loud silliness, starring a family of supernatural weirdos.

Raoul was a werewolf who worked in a factory and ate the occasional dog, while his brother Festus was a Vampire. The infinitely powerful Ginda Bojeffries was perennially single as men found her ability to arm-wrestle the gravitational pull of black holes somewhat intimidating. Oh Grandad is an amorphous mass in the last stages of organic matter.

If this sounds ridiculous that’s because it is. Wilfully surreal and absurd, Moore and Parkhouse crafted a strip that was as wild and fanciful as anything either of them would ever work on, but shot through with rapier-sharp observations on a British working class culture that was already starting to disappear even back then.

Looking back on what has always been one of his favourite works, it’s no surprise Alan Moore has perfect recall of the genesis of The Bojeffries Saga.

Click to enlarge.

“We were working on Warrior. It was the early days and I had a great urge to work with Steve Parkhouse, who I had admired for ages. It was dependent on how much time Steve had got along with writing and drawing his other strip for Warrior, The Spiral Path. Me and Steve decided we’d like to do a humour strip, which seemed to fit in with Warrior as it was a genre missing from the line-up of strips.

So we started to put our ideas together, but in the early days our ideas were a lot more conventional than it actually turned out. For one thing we were thinking of making it an episodic story, like all the other strips in Warrior, with an overarching narrative rather than individual episodes, so to that end when I started to put all the individual ideas together, it was a fairly conventional idea. It was the idea of having, basically, a family of monsters, which wasn’t a particularly new one at the time.”

When influences on the Bojeffries are usually discussed the almost-literal spectres of Munsters and Addams Family are never far away, but according to Moore, while those freaky families had a part to play, the real inspirations came from some less obvious sources.

Alan said: “When thinking of influences, I’d have to include Henry Kuttner’s Hogben family stories. This was a series of really great science fantasy stories with a strange family in America. There was also Ray Bradbury’s The Family, an occasional series that included things like Uncle Ivor Has Nine Wings and things like that, though that not being so comical wasn’t so much of an influence. Of course there were things like The Addams Family, The Munsters and all of those TV monster family shows. but the Henry Kuttner stories were probably at that point the predominant influence.

I was thinking if we took that basic idea but just moved it to England, then surely that would be a big enough difference? It would alter the character and tone of the story enough to distance it from the original. At that point I was still planning on giving a tip of the hat to Henry Kuttner’s original story. I think we ran a preview in Warrior that included a character called Hogben Henry, as we were still thinking of it as an episodic, continuing story. I think he was some sort of American cousin who would have turned up for an apocalyptic showdown in the final end of the arc. Then I actually started writing the story and it turned into something completely different.

It was only a couple of pages in when I realised actually why the story was working and that was because it was set in the English working-class landscape that me and Steve were creating. A family of monsters would just be another family. Most families in their way were completely unique oddities. A family that included a vampire, a werewolf and Christ-knows what wouldn’t be significantly different in that landscape. As the story went on, I realised it was influenced a lot less by things like Kuttner or The Munsters or The Addams Family, but by a lot of the British absurdist playwrights of the ‘50s and ’60s.

I’m thinking things like N.F. Simpson’s One Way Pendulum, a remarkable play that was full of ridiculous and comically absurd elements. There was a psychopathic brother who was training I-Speak-Your-Weight machines to sing in a choir, then he was going to premiere this remarkable creation somewhere in the South Pole, which would be such a novelty that millions of people would go there and they would all have to jump up and down to keep warm which would tilt the world off its axis and millions would die, all because the brother wanted to have an excuse to wear black for the rest of his life, which I thought was just wonderful. All those surreal, absurd British comedies seemed to play more and more of an influence as it went on.

The strip started to take its own character, so by the time we got to the end of the first two episodes(the Trevor Inchmale story), I realised that it wasn’t a continuing narrative and that each episode would perhaps have very little relation to the things that have gone before. They would all be little observations of some element of ordinary life, but through this peculiar lens of the Bojeffries family.”

Click to enlarge.

Moore is a famously collaborative writer and the Bojeffries Saga was no different, with the strip being created by the writer working in close harmony with artist Steve Parkhouse. It’s impossible to imagine either creator not being involved with the story, as each man is as essential as the other to what makes it so unique. Understandably, Moore is full of praise for his long-time collaborator.

He said: “Probably two of the best artists that I’ve ever worked with and two who are very different but both come from the same roots are Steve Parkhouse and Kevin O’Neill, because both of them are unaffected, or apparently unaffected at least, by American comic books that they have absorbed during their youth and then during their career.

You can see they’ve grown up absorbing Leo Baxendale, Ken Reed and all of these great artists for DC Thompson. They’ve sucked up all of this stuff, Steve possibly even more than Kevin. He seems to have came from the same classic tradition of someone like Dudley Watkins. He had his Lord Snooty style, which was perfect for Desperate Dan or any of that stuff, but you also had his serious dramatic style, which was in stories like Jimmy And His Magic Patch, as well as a third style that he used for his religious illustrations. And so it was with Steve.

He has this wonderfully fluid, cartoony style that he showed off to such great advantage in the Bojeffries, but he also had this impeccable dramatic style that he showed off in The Spiral Path (another Warrior strip) and a load of his other work. He was a really great all-rounder, Steve. Yes, the art in Bojeffries was cartoony, but the detail, it was believable, it was credible, it was a recognisable British landscape. Even if it was exaggerated or cartoonified, it was always rooted in reality.”

For all its strangeness, there’s something beautifully relatable to the Bojeffries Saga. Monsters they may be, but there’s a very familiar family dynamic going on in there, while scenarios like dodging the rent man or the dreaded Work Night Out were perfectly pitched little snapshots of everyday life on a working-class council estate. Importantly, there’s no malice or contempt on show from Moore here, as cutting as his wit may be, there’s clearly an affection there for what he has described in the past as his most autobiographical story.

Click to enlarge.

He said: “Well, that is certainly true. To some degree everything you write and even in every character you write, there is going to be a bit of you buried somewhere in there. So in a sense, I suppose all stories are autobiographical to some degree or another, but with the Bojeffries this was taking observations from my deeply-buried memories of a working-class upbringing. It was probably taking memories of a working class world that wasn’t there any more by the time I started writing the story, or at the very least was on the brink of vanishing.

It was a world where I would walk past factories as a child and I would not understand the arcane functions of these factories from the signboards on the gate. There’d be a pile of blue shavings visible through the gate, there’d be a strange smell and it was only later that I would realise that this was some sort of tanning yard. So that was kind of reflected in Raoul’s factory : Slesidge & Harbuck – Staunching, Grinding and Light Filliping.

There were the peculiarities of speech, the little things that your parents or someone that you knew would say. I remember that the expression ‘Duzzy’ that was used in the first episode, that was something peculiar to my first wife’s father, who would use it instead of saying ‘bloody’, or something like that. It was one of those evasive semi-swear words, which I thought sounded peculiar so I stuck it in the Bojeffries. Things like the Batfishing story, that was just trying to convey the sense of these working-class traditions that you were aware of but didn’t understand the reason for it. The normal rituals and traditions that come with an ordinary family life, well they somehow got changed into Batfishing, which seemed emblematic of the ways that British people seemed to pass their time. But yeah, it’s all autobiographical, in that all families look a bit weird and monstrous when you’re growing up in them.”

One of the Bojeffries’ finest moments came in Warrior issues 19 and 20, the masterpiece that is Raoul’s Night Out, where the affable Werewolf enthusiastically throws himself into a work’s party, with typically hilarious results. Populating the story with Raoul’s mostly horrific co-workers and a pair of racist Policemen, Moore gets a laugh out of almost every panel while getting across exactly what he wanted to say.

He said: “I didn’t have to reach back so far in my memory to bring out Raoul’s Night Out. That was thinking back to my late teens and early twenties where I was in the world of work and experienced works nights out for myself, which were always kind of nightmarish, if oddly entertaining in other ways.

I think in that episode I think that I really hit my stride with Bojeffries. That was where I really felt it all crystallised, with that final scene where the Police burst in through the window and there is a ridiculous punk rocker, a teddy boy dwarf, a member of some extremist right-wing fringe group, a werewolf and a black man. Of course they just walk straight over and beat up the black guy. It’s left in the final panels with Raoul still sitting there looking like a Werewolf and Little Nigel the dwarf is sitting there saying ‘Well, y’know, I’m not racial prejudice, but they ent the same as us, are they?’. It was there I thought that was exactly what the Bojeffries should be about, that someone could say that with a werewolf in the room without a trace of irony.

It’s saying something about British culture and it’s saying something about working-class culture, but it feels funny too. It was those sort of things, memories of the August bank holiday fortnight, or the Factory Fortnight as it was called, going to Yarmouth every year and staying in a caravan and walking along the front, all of those things.”

With its first episode coming along in 1982 and the last (so far) set in 2009, Moore has kept the Bojeffries family close to his heart for over 30 years and in that time has, by the very nature of the strip, documented the British working class during that period. Looking back at those early issues, there’s an almost quaint portrayal of a world that time has left behind. It’s something that the writer looks on with some measure of pride.

Click to enlarge.

Alan said: “One of the things that is perhaps the element of the Bojeffries that I’ve ended up being proudest of, because without ever meaning to do it, there is a kind of history of British culture, the incidental British culture that is kind of embedded in that narrative. How long has it been since there was a rent man? Or giro cheques? There’s all these things that don’t exist anymore. Even in the most up to date story, Big Brother is still on Channel 4 and David Cameron is still in opposition. It’s these ephemeral things about our culture and the way it’s changed over the years that end up being the most poignant things about the Bojeffries.”

Appearing in Warrior at the same time as Bojeffries was Moore’s V For Vendetta. A grim nightmare vision of a near-future fascist Britain, the writer extrapolated its politics and ideas from the world around him a the time, making logical jumps to where he could see society going given the right circumstances. Brought to stark life by David Lloyd’s monochrome art, its tone was deadly serious, but only a few pages away, The Bojeffries Saga was making just as pointed and well-observed comments about Britain, but what with being (on the surface at least) a knockabout comedy strip, it flew somewhat under the radar.

Moore said: ”It was always one of the most intense and difficult things to write. Probably the nearest thing in my later career that came close to it in terms of difficulty was Jack B. Quick. Very dissimilar strips, but both humorous, both depending upon dislocating your sense of logic to a suitable degree so that you could actually think in terms of the logic of those characters.

The Bojeffries were kind of like a language that I had to learn to speak with each story. Like Festus: Dawn Of The Dead started off as a title, more or less. I just thought ‘Let’s follow Festus throughout his day and see what happens.’ The first thing that I thought of was that he’d want to be up before sunrise, wouldn’t he? In order to get about his business. I remembered when I used to have to get up early, I’d have the radio by the bed, so I’d always hear Thought For The Day, which is at 6 in the morning, a five-minute long, tiny little religious programme, which would generally be some Church of England vicar who would come up with a loveable character with which to explain the delights of Christianity. That kind of got worked in there.

By the time he got to the shops I’m thinking (and this is another example of how it comments upon things that aren’t really noticeable any more) that I remember at the time there weren’t really distinctive shops any more. There used to be a sweetshop, a greengrocers etc and I was starting to notice that recently everybody now did a bit of everything, so I came up with Rosemary’s Whole Foods, Fishing Tackle and Adult Video, which sounded like a comical exaggeration at the time, but these days you probably wouldn’t blink if you saw it. But I was having to get myself into that frame of mind, where I could make observations like that, where I could think ‘what would Uncle Raoul do?’.

Probably the character I identified most with was probably Ginda Bojeffries. I always had a great liking for her as she’s so very confident, while Raoul has always been adorable. It was just a matter of putting a different head on to work with them.”

With Warrior folding, the Bojeffries lost their home and spent the ‘80s and ‘90s making occasional appearances in titles like Flesh & Bones and A1, the latter containing new stories, but from 1991 onwards, we thought we’d seen the last of our favourite family of monsters. But we were wrong. In 2013, Top Shelf Productions and Knockabout Comics combined to release a beautiful collection of the complete Bojeffries Saga that featured an all-new 24-page story that brought us right up to date. Well up to 2009 when Alan wrote it. A lacerating broadside on the vapid celebrity culture that Britain had taken to so wholeheartedly, ‘The Bojeffries Saga: After They Were Famous’ was a fitting finale for a story 30 years in the making.

Click to enlarge.

He said: “I’d got to be thinking I really, really liked the Bojeffries and I was sort of sorry that I hadn’t had a chance to do it for a few years. I started thinking maybe it would be nice to bring out a collection again as it’s one of the works I’m most proud of. It is probably one of the works that has received the least attention, although amongst the people who have paid it attention it’s often one of their favourite books of mine. It’s amongst my own favourite works too, because it’s coming from somewhere that is very personal and it’s about something that seems to me to be real and relevant.

Working class life is an area that isn’t discussed or bothered about enough for me, but it seems to me to be important. Bojeffries has always had that incredible importance to me, so I thought it would be nice to bring it out again in a collection and I then thought it would be good to give readers something new and substantial, so what about a story about where Bojeffries are today? They’ve obviously not aged, as they’re probably thousands of years old anyway, doesn’t matter, they’re immortal! So what are they doing now in this very different world?

The first thing i thought of is that Ginda Bojeffies would almost certainly be one of Blair’s Babes, a kind of Ann Widdicombe of the Left. Once I had that image in my head, the rest of it started to fill itself in. I came up with the idea of Reth, the eternal 11 year-old, in the Groucho Club, or at least a close surrogate of it, having published his memoirs. All of these ideas were floating around, so I just sat down and pulled out a piece of paper and the very first thing that occurred to me was that it would be good to start all this as a TV retrospective and I came up with that opening sequence, with the upside-down view of the Gallows and that Geordie bloke doing the voice over.

The thing is, all of these things completely dates the story. Will anybody in the future have any idea what that is about? Probably not, I just hope it’s still funny! I barely bothered planning the story out in advance, I just started from that first page and went onto the next, in the way that you let one note follow another in music. There was something very musical about the way that i composed the Bojeffries and of course there was something incredibly musical about Steve’s artwork, it’s got that lovely springy, expressive cartoon style. When I mentioned it to Steve, fortunately he was as up for doing it as I was. It took a while, because he has a lot of commitments, but the end result was absolutely stunning. I did wonder whether we might have paled a bit compared to the original strips, because it’s about 30 years later. You can’t help but worry if the later ones would seem as fresh as the first ones, but I think that it does. Yes, it’s different to all the others, but it stands up. It’s got everything that the others has got and it retains its freshness.”

After They Were Famous still felt very like a Bojeffries story, but the years had changed both the family and the writer. There was a certain acerbic quality present, a cynicism that seemed more pronounced than it had been in those early tales. Comparing the two, Moore is very aware of the difference in tone.

Click to enlarge.

Alan said: “A lot of the earliest stories have a cynicism in them, like Raoul’s Night Out and the racism that was endemic both in the country in general and in the police force. There’s always been a cutting edge to the Bojeffries, but generally in the early stories, the humour is probably more affectionate, I think. Even while I am rueing the horrific institution of the works night out, I can still find something kind of dopey and endearing about it, whereas in the later ones, and this probably reflects the 30-odd years the story has taken to unfold, British society has changed a hell of a lot and of course so has the individual who was writing it! I’m 30-odd years older. My attitudes have changed to a certain degree.

I don’t think I get more right-wing as I get older, though saying that I have a copy of a Max Hastings book on my table next to me. It’s one of his war memoirs, which are actually quite good, it doesn’t mean I’ve started reading the Daily Mail. I have perhaps become less tolerant about some of the things that I think are ridiculous or even repulsive about culture. Obviously I wasn’t a big fan of the shallow culture as represented by Big Brother at the time, which we used as a convenient and easy target in that final story.

So yes, it has become more acerbic. A lot of that episode is talking about culture, from the popular arts programme that frames it, to How To Look Good Naked, to Hollyoaks. It probably unfairly focuses on Channel 4, actually! Lord knows, there are probably more deserving victims of that scorn, but they were doing Big Brother at the time, so if the cap fits and all that.

Most of my scorn is probably reserved for that kind of celebrity culture and of course there is a fair bit of withering scorn towards Hollywood in the ‘Meet The Bojeffries’ sequence. That is probably born of my own experiences within the film industry that have taken place since I began writing the Bojeffries back in 1982.”

Acerbic it may be, but After They Were Famous is still loaded with poignant little moments, including one that Moore found a different meaning in after it was written.

He said: “One of the things in that final story that stuck with me was when Uncle Raoul was on his way to the Big Brother auditions and there’s just a shot of him walking down a flooded street, up to his waist in water, with all the Police rescue boats helping people in the background. Then in the next panel he’s in a different part of town, where he’s dripping wet but there’s no water. He doesn’t appear to have noticed the town is flooded, because he wouldn’t, as he’s Uncle Raoul.

On the other hand there was something in that panel that seemed to me to speak to the fact that the landscape around us is altering now with blinding speed and we take that blinding speed of change as the norm and we try to deal with that and get along as normal, even if the situation around us is becoming increasingly abnormal. I know that’s a lot to read into a single panel and it was certainly not what I intended when I wrote it, but the way it came out there was something poignant in that, that we are walking through a flood without a care in the world.”

After They Were Famous was written as a finale to the Bojeffries Saga and as such it works perfectly, in as much as an immortal family of supernatural monsters can ever be seen to have an ending. If this is really the end, it’s a good one. Alan Moore however, isn’t ruling out the possibility of another appearance by the Bojeffries somewhere down the line.

Click to enlarge.

“Well, I got a lovely letter from Steve the other day. Who knows? As always with the Bojeffries, they’re kind of spontaneous. They first appeared in Warrior when Steve and I both had the time and the inclination and they just felt right. We got an idea for a Bojeffries story when Garry Leach was doing A1, where the thought of a few little short, self-contained Bojeffres stories might be quite fun. When that stopped happening, then we were both otherwise employed for a number of years until eventually the Bojeffries called us back again. Whether there is another story there? I don’t know. If one does arrive I’m sure both me and Steve will recognise it and respond to it. I didn’t know that the last time was going to happen. If it ended there I wouldn’t be displeased, but on the other hand, if me and Steve did happen to come up with another idea in the future, I would be even more pleased.”

So there you have it. It’s not a competition, with one comic “better” than another, but Bojeffries Saga is every bit as inspired, every bit as special, every bit as flat out wonderful as *anything* Alan Moore has ever written.

Think about that for a minute.

Now, if you haven’t already, go discover it for for yourself. And be ready to fall in love.

The Writer of this piece was: Jules Boyle

The Writer of this piece was: Jules Boyle

Jules tweets from @Captain_Howdy

Leave a Reply